US Stock Options Primer:

Key terminology:

- Option — The opportunity for employees to purchase a fixed number of shares at a fixed price at a fixed point in the future;

- Grant — When an employee is offered a specific number of options;

- Exercise — The point at which an employee purchases shares and actually pays the strike price in return for owning shares;

- Strike price or exercise price — the cost of purchasing a single share;

- Fair market value — the actual value of the share. For listed businesses this would be the share price but this is much more difficult for unlisted companies to approximate. This is normally linked to the latest external valuation or set in a 409a valuation for US companies;

- Spread — The difference between the exercise price and fair market value. In many ways this is seen as the gain or profit made on each share; and

- Vesting — the time after which an employee can exercise options. Typically a vesting schedule will specify that of the granted options a proportion will vest, and can be exercised in increments. For example for 100 shares on a four year vesting schedule; 25 shares can be exercised at the end of year one, two, three and four.

Synchronising the UK and US option plan

Most UK founded companies launching in the US will have a wholly-owned US subsidiary. As a result, most employees, whether UK or US will want to have options in the US parent company as that is where the ultimate value will be. This structure of option pool is the most common from what we have seen.

The complexity of having US employees with UK options, comes from ensuring that it is structured so that it remains tax efficient. US permanent employees will be governed by US tax law irrespective of where the parent company is. In the UK, the EMI (Enterprise Management Incentives) scheme shields UK employees from capital gains taxes up to certain thresholds. The US equivalent is an ISO (Incentive Stock Option) and has similar intentions as EMI but is unfortunately less tax friendly to the recipient.

HMRC has a specific process for establishing what is deemed an appropriate exercise price for options. The IRS (US Internal Revenue Service) has a different process. The challenge arises when trying to synchronise the exercise price in both geographies as otherwise you will be incentivising employees holding the same number of options differently across the organisation. Where this inequality has happened, it has been a sensitive issue to remedy which could be avoided entirely with adequate planning.

How EMI works in the UK

Under the EMI scheme a company can “self-assess” to set up the plan and HMRC should be notified whenever options are granted. There are annual limits for participants and a restriction on the total value of options in the pool. The exercise price must be agreed with HMRC in advance to ensure that the tax breaks are achieved. The exercise price for ordinary shares (typically the share class for options) can be at a discount to the share price for preferred shares and this discount is can be up to 70% or more. The valuation methodology and calculations are normally sent to HMRC as part of a short one to two page letter. HMRC valuations are typically refreshed after a funding round or if company performance materially changes. HMRC valuations can only be agreed when new options are to be issued — HMRC will not do “speculative” exercises to try and gauge a likely price.

How “stock options” work in the US

One pre-requisite for an option plan in the US is a company valuation (409a valuation). In addition, at the time of each option grant, companies will need to update the 409a valuation. This can be done in-house but it is advised that companies outsource this. If a company completes the valuation in-house and the IRS scrutinises the option scheme, the onus is on the company to prove the methodology. If the 409a is done externally, the burden of proof is on the IRS who must disprove it. A 409a is typically a 10 page report with supporting calculations and methodology.

If the valuation is conducted externally by a third-party this is typically completed by a specialised assessor or accountant. This can typically cost $2–5k for a full valuation exercise depending on the complexity. Some banks such as Silicon Valley Bank also offer this service — contact details below.

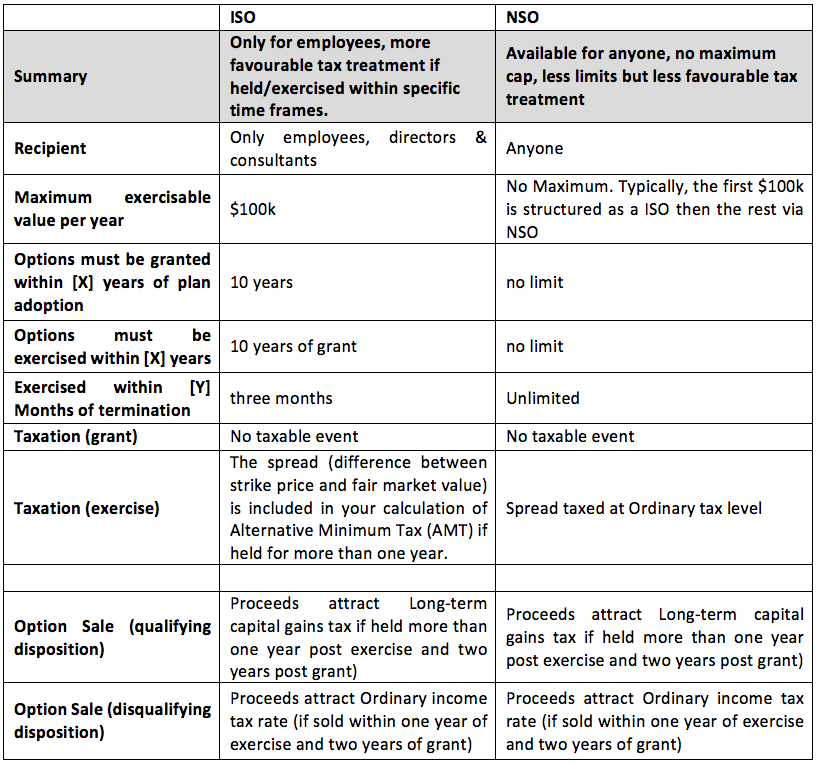

There are two main categories for option plans in the US; ISO (Incentive Stock Options) and NSOs (Non-qualified Stock Options). The ISO is the closest equivalent to the UK EMI scheme. The differences in both US structures are laid out below:

For reference, in 2016:

- Capital gains tax was up to 23.8 per cent;

- Long term capital gains was up to 15 per cent; and

- Ordinary income tax rate was between 10–39 per cent.

For companies that already qualify for the UK EMI scheme, many will also qualify for treatment as an ISO in the US. This is however worth checking with your US lawyers.

Tax implications for employees

When employees exercise their option grants, this will attract tax. For an ISO this can be in the form of AMT or for NSOs this will be Ordinary Income Tax. Typical employment contracts restrict employees exercising their options beyond 90 days from termination which can amplify the tax impacts as a decision to exercise options must be made promptly.

Employers looking to give employees more flexibility in exercising their option grants sometimes increase this period or convert the ISO to a NSO with no limits on when options must be exercised by. If an option is not exercised after three months of an employee leaving a company, it will no longer qualify as an ISO and will be treated as a NSO for tax purposes if the options do not expire anyway after three months. In the example of Pinterest and Quora where they extended the post-termination exercise window, these options automatically converted to a DSO after three months and employees were able to exercise options up to seven years after leaving the company.

For example, some companies have said that for employees that have worked in the company for two years, they will have up to two years to exercise their options. This delays the point at which the employee will have to pay the strike price and tax when exercising options. Otherwise the tax bill can be significant given that the tax will be calculated on the spread, which may be very large on a fast-growing company and many employees will not be able to immediately cover this. This is especially important for companies where there may be a long period between the exercise of options and a potential liquidity event.

A good worked example of this can be found in the YCombinator blog below.

How many options should I give?

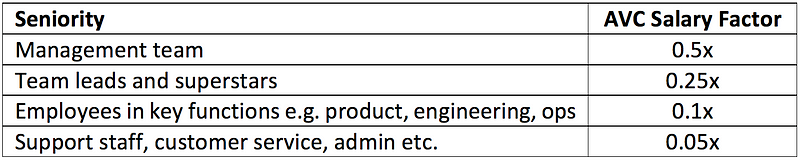

In terms of how to work out what quantity of options is appropriate for specific members of the team, there are many strategies including Fred Wilson’s tiered methodology, summarised below:

Fred Wilson’s approach involves giving an employee a proportion of their salary in option grants. The number of shares is worked back from the “Best Value” which is often the valuation at the most recent funding round. Many companies choose to adjust the salary factor depending on how competitive the local hiring market e.g. some companies multiply the AVC factor by 1–3 x.

Some companies will also look to trigger top-ups when vesting period nears the end as this is arguably when an employee is at their most valuable and most likely to consider leaving.

Other adjustments may typically be made for:

- Experience

- Seniority

- Time of joining

- Impact to the Company e.g top 10 per cent of employees perhaps receive a bonus grant of up to 50% of salary

- Triggering options after a specific tenure — See Andy Rachleff’s blog on Evergreen grants which all employees get after 2 ½ years’ service; and

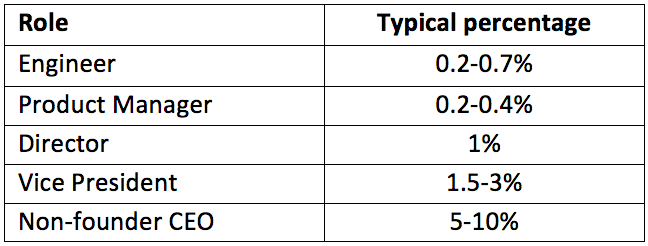

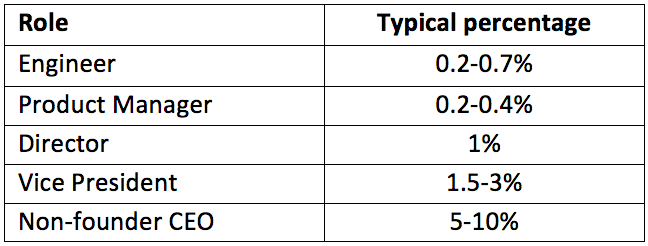

For more senior hires, the % salary method is sometimes harder to apply and employees will have different expectations. Such employees may think in terms of a total ownership percentage of the business rather than as a proportion of salary. These numbers are subject to many adjustments but Guy Kawasaki has suggested the following:

Fred Wilson’s approach involves giving an employee a proportion of their salary in option grants. The number of shares is worked back from the “Best Value” which is often the valuation at the most recent funding round. Many companies choose to adjust the salary factor depending on how competitive the local hiring market e.g. some companies multiply the AVC factor by 1–3 x.

Some companies will also look to trigger top-ups when vesting period nears the end as this is arguably when an employee is at their most valuable and most likely to consider leaving.

Other adjustments may typically be made for:

- Experience

- Seniority

- Time of joining

- Impact to the Company e.g top 10 per cent of employees perhaps receive a bonus grant of up to 50% of salary

- Triggering options after a specific tenure — See Andy Rachleff’s blog on Evergreen grants which all employees get after 2 ½ years’ service; and

For more senior hires, the % salary method is sometimes harder to apply and employees will have different expectations. Such employees may think in terms of a total ownership percentage of the business rather than as a proportion of salary. These numbers are subject to many adjustments but Guy Kawasaki has suggested the following:

There are also many schools of thought on who options should be made available to. Some companies offer them to every member of staff, and others to only more senior roles. Considerations here include:

- Administrational burden of managing the option plan;

- The challenge of communicating the potential value of the options for those with relatively small proportions;

- Making options contingent on achieving specific targets; and

- Creating a culture where everyone “thinks like an owner.”

What you should put in place

- Ensure that a 409a valuation happens as part of your process of setting up in the US. This will enable that the strike price of the US options is synchronised from the start;

- Ideally have a specific methodology or calculation that you use to decide how options are awarded. Moving away from the concept of ownership percentages and towards a scalable approach, ideally just a calculation, will avoid difficult conversations about discrepancies within the company;

- Understand any potential challenges you are creating for your staff in the future by how your option exercise process works, especially the timeframe after termination in which they can still exercise them; and

- If you have ex-employees holding shares, be mindful of information rights and any other complexity this may cause further down the line or at the point of exit.

Pitfalls to avoid

- Trying to retrospectively synchronise two different strike prices as these are set by different processes (IRS and HMRC). This can become a painful issue and if companies synchronise valuations at the point of setting up the US entity this avoids a lot of complexity further down the line;

- If it is deemed that the strike price was wrong when shares were issued to employees, the tax implication will need to be deal with by the employee not the company. An example is given here towards the bottom of the article;

- Think carefully about the impact of conducting 409a in-house rather than using a valuation expert in terms of where the burden of proof lies;

- Not having understood the tax impact of an employee looking to exercise an option grant; and

- Understanding the relationship between UK and US option plans and ensuring that the pricing remains equal and culturally acceptable in each location.

Where to go next

- Great Article on ISO and tax from the Y Combinator forum;

- Very simple infographic on 409a valuations and relationship between the strike price of Ordinary and Preference shares;

- How Pinterest enabled employees to exercise options they had earned upto 7 years after leaving;

- Some great principles from Andy Rachleff on the Wealthfront equity plan — link;

- Difference between ISO and NSO — link;

- Fred Wilson Blog on Strike price — Link;

- The Wealthfront Equity plan presentation; and

- Guidance on how much equity to give advisors and template engagement docs put together by the Founders Institute and Orrick.

Setting up and maintaining an option plan typically involves input from lawyers, accountants and valuation experts. We have worked closely with the following people:

The following lawyers:

- Daniel Glazer, WSGR;

- Tom Michael, Dentons;

The following tax specialists and accountants;

- Eric Collins, Frank Hirth;

- Don Dismuke, Dixon Hughes Goodman;

- Greg Capitalino, Kranz Associates;

The following valuations experts;

- Tony Hindley, Valuation Solutions Ltd — specialising in UK & US option plans; and

- Alexander Ardente, Silicon Valley Bank;

Please send us your thoughts on the above and to highlight your own experiences if these differ from the above! Alternatively email me or Alliott directly.

Thanks to Dan at Iovox, Daniel Glazer at Wilson Sonsini and Tony from Valuation Solutions for helping share your knowledge and experience on this topic.

This blog and those in this series are aimed at helping entrepreneurs learn about the US market, what it takes to start here, and ultimately what it takes to succeed here. Many of the topics (if not all) are complex and it is best to view these blogs as a basic introduction from which you the entrepreneur must triangulate to your own specific set of circumstances — and invariably it will be sensible and appropriate to seek third party professional advice.