Singapore and the Shifting Sands of Future Global Markets

“It is always wise to look ahead but difficult to look further than you can see.” -Winston Churchill

Singapore’s name has cropped up a few times recently, as British politicians and the media speculate on the U.K.’s post-Brexit position in the world. The Southeast Asian country has been heralded as an example of how enduring economic success can be created against the odds.

So how has Singapore achieved this reputation, and can it continue to be a magnet for companies from around the world who have set their sights on expansion into Southeast Asia?

Emerging Giants

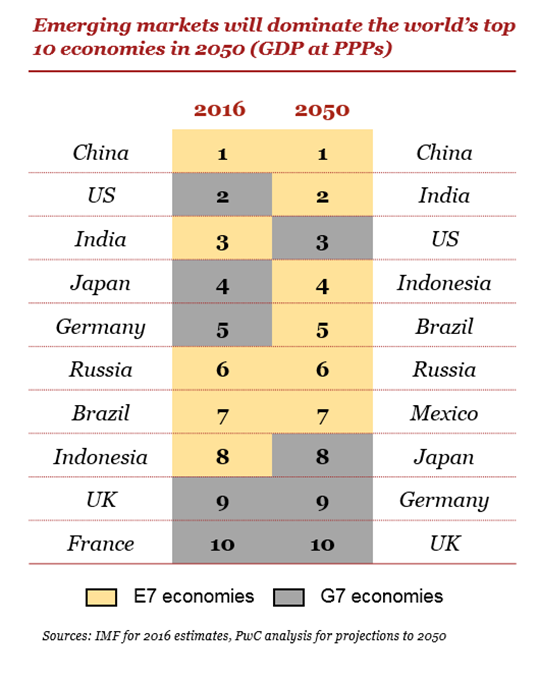

Looking at current predictions of future global economic trends, it is no surprise that many Western companies are looking towards the Asian region for longer term growth opportunities.

According to PwC’s World in 2050 report¹ the key “E7” emerging markets could grow around twice as fast as advanced G7 economies between now and 2050, with six of the seven largest economies in the world projected to be so-called emerging economies, led by China (1st), India (2nd) and Indonesia (4th).

While China and India usually grab the headlines among this elite E7 group, the countries of Southeast Asia are also increasingly attracting the attention of globally ambitious Western businesses.

The fast developing digital economies of this group of countries have been a key reason for this. Indeed, a 2016 study produced by Google and Temasek found that the region is on course to create a $200 billion internet economy by 2025.

In their more recent “e-Conomy Southeast Asia Spotlight 2017” report, Google and Temasek estimate that there are a total of 330 million monthly internet users in Southeast Asia at the end of 2017, an increase of more than 70 million since 2015, with more than 90% of those users on smartphones.

Not surprisingly, venture capital deal activity has seen a sharp increase also, with almost US$13 billion invested in Southeast Asia’s startups between the start of 2016 and the third quarter of 2017².

With a population of 260 million, a burgeoning middle class, and rapidly developing digital ecosystem, Indonesia continues to attract strong interest.

Meanwhile Vietnam, a close neighbour of Singapore, is expected to be the highest climber in PwC’s forecast of future global economic rankings, moving up from 32nd to 20th place by 2050. Likewise, the Philippines is expected to surge up the rankings from its current 28th to 19th place.

Behind those impressive growth figures there are however important economic, political and cultural differences between the countries of Southeast Asia which newcomers should factor into their thinking from the outset.

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations, or ASEAN, was formed in 1967 to promote political and economic cooperation and regional stability across Southeast Asia. More recently, the ASEAN Economic Community, or ASEAN EC, was launched in December 2015 with a view to greater economic, political and cultural integration among its 10 member states of Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam.

With protection of valuable intellectual property and data a high priority for most British companies, certain members of the ASEAN EC have made significant progress in recent years, although a unified legal framework similar to the European Union is yet to be introduced across the region, and free movement of workers is also a significant challenge. Many inbound companies therefore decide to establish a trading hub in a location such as Singapore, which can provide a robust platform for their business activities across the region.

Singapore: the “Smart Nation”

Ranked second in the world for ease of doing business by the World Bank, Singapore has overcome a lack of natural resources and its small size to position itself as a key business gateway to Southeast Asia during the five decades since gaining its independence.

Singapore’s economy grew quickly during its early years by manufacturing goods cheaply. The production of silicon chips and disc drives followed in the 1980s, while the 1990s saw the service economy in the ascendant as Singapore established a global reputation, attracting international talent and placing it among the leading rank of emerging economies.

Now a highly developed economy, over 7,000 multinational companies have opted for the “Little Red Dot” when looking to access the dynamic markets of Southeast Asia. They like its advanced infrastructure, business-friendly tax regime, robust legal system and educated workforce, supported by a government committed to creating a seamlessly integrated and connected “Smart Nation”.

In common with the U.K. however, Singapore faces its own challenges in remaining competitive as a business hub for the future. The rapid economic growth that characterised its first decades could not continue forever and, as other Asian countries make their case for attracting inward investment, Singapore is working hard to stay on top.

Predicting the Future

Singapore relies upon global trade to a much greater degree than most other developed countries, exporting goods and services worth the equivalent of 172% of its GDP, according to the World Bank.

In turn, this makes the economy more sensitive to macro-economic trends than other countries. When the big global economies sneeze, Singapore tends to catch a cold.

Singapore’s leadership therefore recognises the need to make a series of “calculated bets” in order for the city state to remain competitive in the global marketplace, keeping its doors open to international trade, as well as the best talent and innovation.

The Singapore government’s latest Smart Nation master plan is designed to ensure that the city state builds on those strong foundations and remains competitive in the modern digital world, with initiatives such as the US$19bn Research, Innovation and Enterprise Plan aiming to maintain Singapore’s world leading reputation as a tech enabled business hub of choice.

Over the longer term, the growing success of neighbouring countries such as Vietnam and Indonesia may create a bigger economic “pie” for everyone, including Singapore, if all are able to resist protectionist policies in favour of free trade. But this will take time and it is reasonable to expect a steady but not dramatic pace of change over the next decade.

In the meantime, companies looking to set up operations in Asia can benefit greatly from thorough testing of the market fit for their products and services, assessing the regulatory and operational risks properly and above all finding the right people to grow their business on the ground.

In the midst of a fast evolving region, Singapore’s government continues to plan meticulously for an uncertain future. British companies coming into Southeast Asia would be well advised to do the same.

HENRY GOODWIN

Henry has been based in Singapore since 2008, where he has built and led multi-disciplinary teams focused on helping investors and corporate clients to execute their growth strategies in Singapore and Southeast Asia. He is currently a Partner leading the Digital and Technology team at PwC Legal International in Singapore and a Venture Partner at Octopus Ventures.