Value chain teardown: Pensions

There is over £6 trillion of funds held in UK pensions, yet these assets are largely trapped in a set and forget model when it comes to customer engagement. The implications of poor stewardship are huge when considering people are living longer and will need to rely more and more on adequate retirement income. Auto-enrolment brought about revolutionary reform and has paved the way to 10 million new savers since launch. Auto-enrolment was critically important as the first step to individual pension objectives, but the way we interact with our pension remains antiquated. Can the new wave of personalised fintech investment platforms in the workplace create a culture of increased individual investor engagement with better outcomes for our pension objectives?

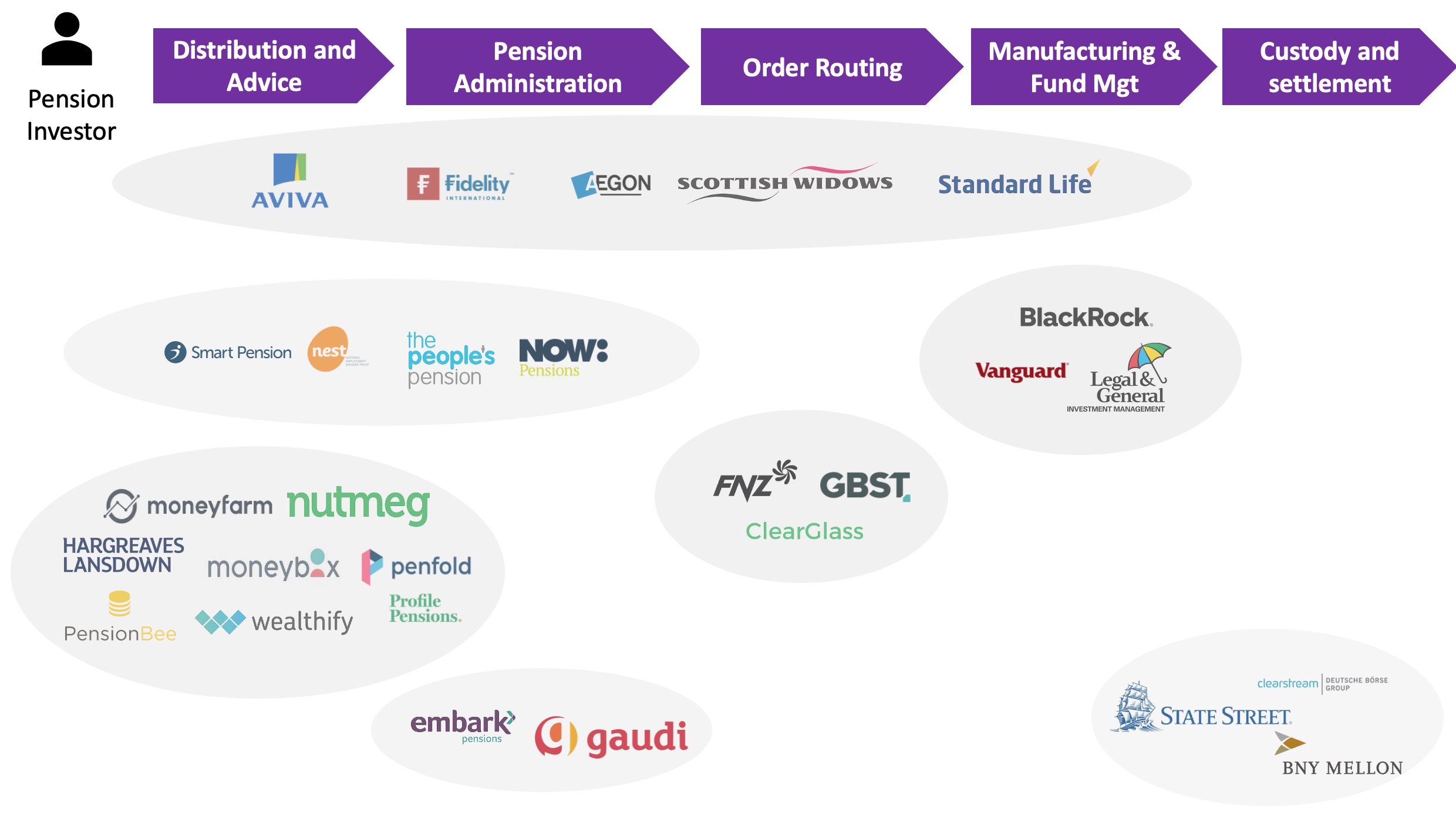

Let’s start by breaking down the pension value chain:

Top layer – Distribution and advice

Advised (higher margin and higher fees) or non-advised (lower margin and lower fees)

Mainstream model

This part of the value chain is characterised by high customer acquisition costs, long payback periods but lucrative customer lifetime values. Distribution is queen and companies who have cracked this, such as Smart Pension, have scaled their assets under management significantly. Insurers have had historical success given their ability to cross sell into their customer base.

Due to the falling costs of building and maintaining a pension service, we are starting to see hyper focussed pension providers going after underserved demographics. Penfold is an excellent example of this as they are targeting the 5m self-employed workers who do not save into a pension pot. But I’ve yet to see a pension service targeting the elderly who are sitting on the most significant chunk of pension assets.

B2BC model

These pensions are typically distributed through large corporate pension schemes and are often sold to satisfy the pension regulators. They are typically built on legacy technology and result in a poor digital offering. The operational cost of running these pension schemes is high and as a result they do not target consumers directly as the cost to serve an individual is not economically feasible. That said they are deeply embedded with their corporate customers and do not face pressure to invest in product improvements.

Direct to Consumer model

These pension products are generally targeted at engaged individual investors or active self-employed workers. Robo-advisors such as Moneybox let savers personalise their pension to fit their lifestyle. SIPPs allow individuals to choose their investments directly. Traditional IFAs also engage in this space but generally charge higher fees and thus serve a more minor part of the market.

The unit economics for targeting individuals rather than distributing through the workplace remain to be proven. Many providers will try and aggregate your existing pensions to generate a higher annual revenue per user. It is also not unusual for players in this space to require minimum pension amounts. I expect these minimums to fall away in the short to medium term as the infrastructure costs continue to fall.

Middle layer – Infrastructure

High Volume – Medium Margin

FNZ and GBST are the two main providers of transaction aggregation for fund managers. Calastone is the main provider in the UK and to many other countries and territories of order routing of transactions to the fund managers. Both FNZ and GBST have built highly profitable businesses due to limited competition (high network effects) faced in this part of the value chain. FNZ and GBST have benefitted from network effects as there have been few new entrants into this space.

In 2019 FNZ was set to acquire GBST for £150m until it was blocked by the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority.

We are starting to see more scrutiny on the performance of fund managers as the data is becoming more widely available. ClearGlass is an example of a start-up shedding light on the cost structures and performance of pension fund managers.

Bottom of the stack – Fund managers

Very High Volume – High Margin

The majority of UK pensions are held with BlackRock (40% operating margin!), StateStreet and Legal & General. BlackRock has been more pioneering on the risk adjustment front and allows pension administrators to offer the end customer the ability to switch risk levels on their pensions with relative ease. It is widely known that the margins for pension fund managers are under pressure (hence the need for ClearGlass). There is a trend of pensions being put in market index funds which have lower operational costs but generate lower margins.

What is on the horizon?

- Reduction in tax benefits particularly for the higher earners

The government has floated around a number to the tune of £10bn worth of savings by changing the pension tax benefits for high earners. The focus has been on scrapping the 40% tax relief (tax relief contributions are paid in at the highest rate of income tax you pay) on pensions offered to high earning pensions. On the flip side the tax savings could become better for the least well off to incentivise further saving for the future.

- Open pensions

Visibility into individual pensions and pension migration has long been deliberately obscured by the providers to escape performance evaluation and to lock-in customers. We can expect to see something akin to the open banking push in the pension where transparency, cost, comparative performance and portability will become evident. This should make it easier for savers to see balances, aggregate pensions and change pension providers.

Pensions are just another form of savings but have long been looked at in a different light. Ask your friend how much they save a month and I’d be surprised if they factored in their employer pension contribution. As fintechs empower users to take control of their entire financial self I expect pension savings to be brought more front-of-mind. Investment platforms may help you better allocate your pension risk and/or facilitate equity release for later stage pensions.

- Auto-enrolment for the self-employed

Surprisingly, 95% of the 5m self-employed workers in the UK do not contribute to a pension. In 2012 automatic enrolment for pensions was made mandatory for all workplace employers. Given that the self-employed segment now makes up more than 25% of the UK labour force I would not be surprised if the government brought a similar ruling out for this sector.

Concluding Thoughts

There is no doubt that the pension industry is ripe for disruption, just as the banking industry was 15 years ago. Challenges to newcomers include the technological capabilities to offer open and flexible platforms to facilitate account transfers for a range of needlessly complicated legacy products and, equally important, a customer interface protocol which complies with strict regulatory requirements. The pension industry has learned that complexity and obscurity limit competition and these characteristics have been built into pension systems from top to bottom. Overcoming the dark forces of the pension empire will not be easy, but that’s what revolutions were made for.