It’s time to rethink growth investing

The current state of IPO markets — the year the music stopped

The period between 2019 and 2021 saw an impressive broadening in investor enthusiasm towards exciting, tech-enabled businesses as Covid accelerated the utilization of remote technologies, much to the benefit of companies already harnessing those concepts as part of their core business models. This optimism resulted in the widest valuation gap between growth and value stocks we have seen in the last 20 years1. Consequently, we also saw a buoyant IPO market for growth companies in particular, both through traditional listings and also through special-purpose acquisition company (SPAC) activity.

Three sectors dominated public listing activity: 1) finance, 2) technology, and 3) healthcare & life sciences. These areas combined accounted for over half of all global IPOs in 2021, and raised more than half of the total proceeds. Within the global healthcare sector specifically, 2020 and 2021 saw record levels of activity in IPOs, with a combined $101b raised across 669 offerings in 2020 and 20212. That is nearly double the amount raised in the four years between 2016 and 2019 ($64.93b) across a not-too-dissimilar number of companies (733). In contrast, YTD in 2022 we have seen $13.6b raised across 119 offerings in the healthcare and life sciences space.3

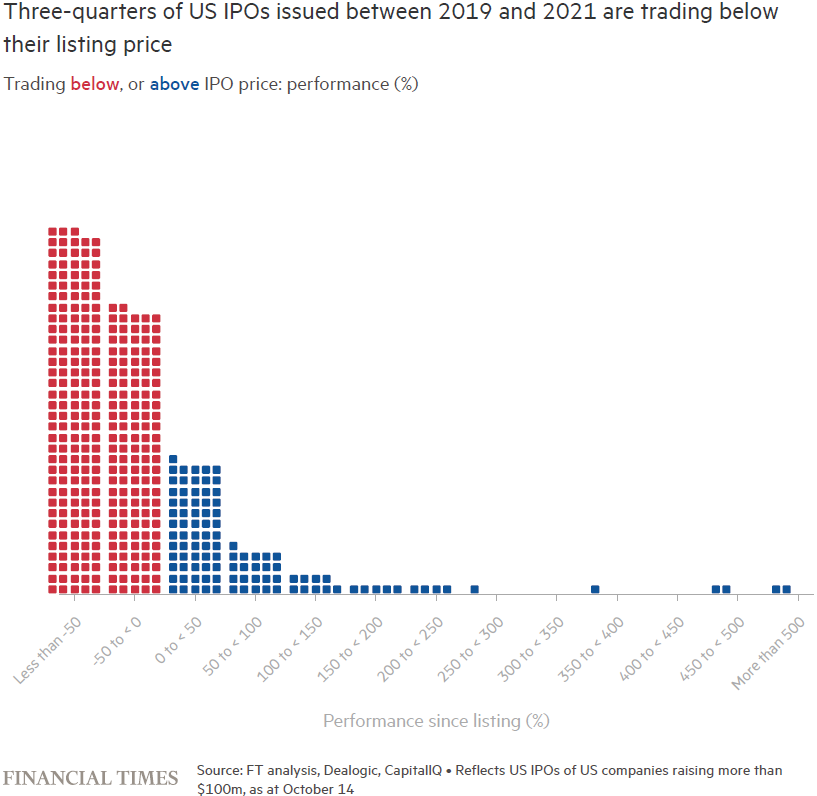

That same period between 2020–21 saw more companies being brought public at inflated valuations during the SPAC craze than at any time since the Internet Boom of the late 1990s. Within this context, what can at first glance be viewed as a plummeting IPO market is, in reality, more of a mean reversion and a return to more normal levels of activity. With the benefit of hindsight, we can see that the temporary market optimism we experienced in this two-year period was due entirely to the perception of stability created by central banks around the world, propping up economies and providing unprecedented monetary support in the form of practically unlimited capital. But now the macroeconomic environment has changed drastically, bringing about a significant rout in growth stocks, and leaving behind an altogether different landscape. What we are now seeing is that of >400 listings where companies raised at least $100m between 2019 and 2021, 76% are now trading well below the price at their IPO. The group’s median return since their respective IPO dates is -44%4.

So, what caused this? The current backdrop of severe economic uncertainty is, without doubt, a significant driver of unfavourable generalist sentiment towards growth companies more broadly. The record bull market in the decade following the financial crisis was certainly due a correction, and levels of inflation not seen in decades have unsurprisingly added up to form the straw that broke the camel’s back.

A large portion of the extreme post-IPO price fluctuations have taken place during a period overcome with significant and chaotic investor shifts away from growth stocks and toward value stocks, therefore it is possible that the newly listed companies were simply unlucky enough to be in growth sectors just as investors were shifting away from them. But given the severity of the peak and subsequent trough in investor interest, there appears to be a more structural issue at play: does the perception of investing for growth require an upgrade for the 21st century?

Staying private for longer

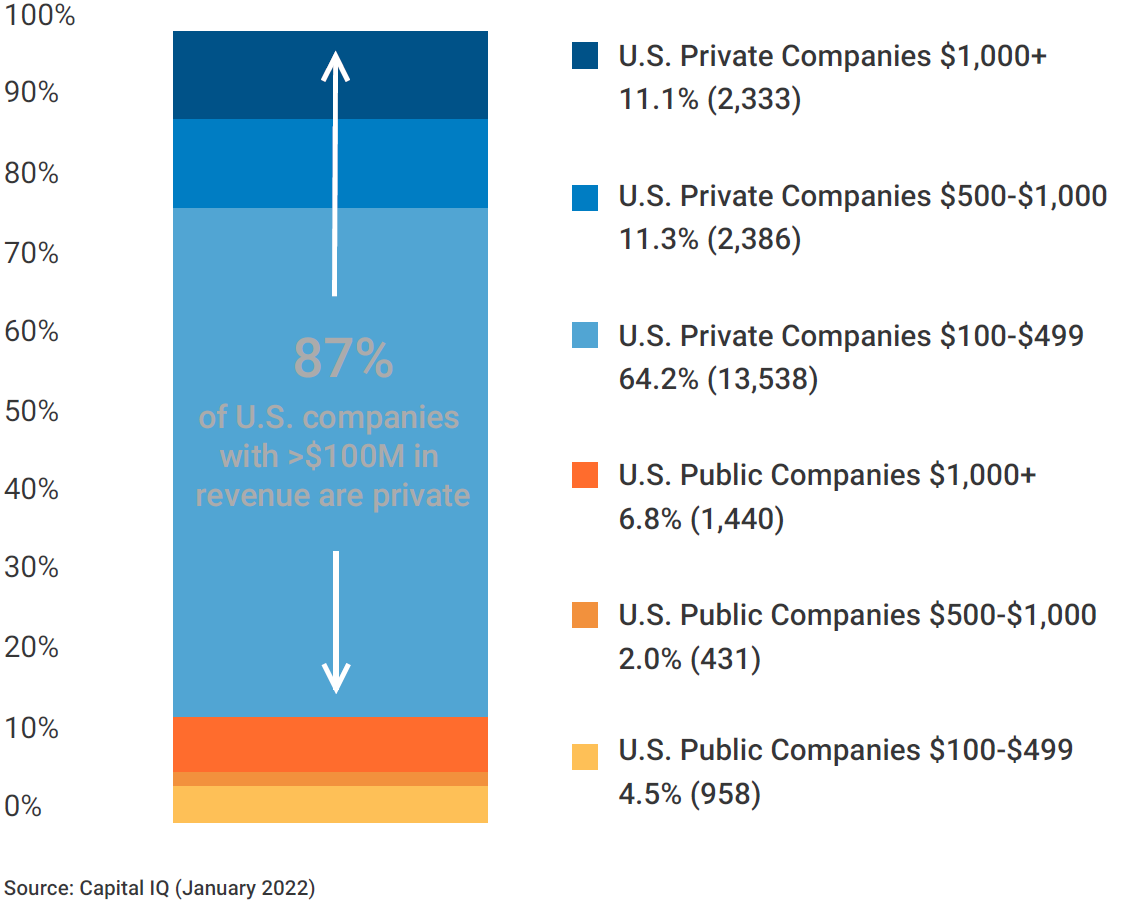

While in the past investors participated in IPOs in the hope of taking part in a company’s ascent to a double-digit billion-dollar valuation, times have changed, and expectations of outsized returns and exuberant levels of growth post-IPO are no longer realistic, as those types of returns are now taking place outside the realms of public markets. The issue is that often, investors with this expired mindset don’t realize that they’re boarding the lift at the top floor, which then leads to a spiral of poor share price performance driven by overly punitive market reactions to unmet results expectations. Therefore, the way to update the ethos of growth investing for the 21st century would be for investors with sufficient risk appetites to look to private markets for the opportunity to take part in companies’ growth at an earlier stage of their development.

In 1999, the average age of a US technology company going public was 4 years. By 2020, that had increased to more than 12, as private funding rounds have generated an increasing number of unicorns (meaning companies reaching private market valuations of >$1 billion). Technology-driven companies in particular have seen a material shift away from public markets, instead tapping into private capital for funding. A study of unicorn companies has found that around 60% of them stay private for at least nine years5. Essentially, that is not only long enough for a business strategy to develop, it’s long enough for full-scale disruption of an industry to take place before the company ever experiences its IPO. Take Uber and Airbnb as an example — these companies waited 10 and 12 years, respectively, before going public in two of the largest-ever tech IPOs. By that time, they had already largely displaced incumbents in their industries.

The abundance of private sources of capital means start ups can afford to stay private for much longer, and go through substantial growth phases before turning to public markets as an entry into their more mature stages. As equity and bond markets forecast a continuously choppy outlook, with a recession looming on the horizon, in an act of self-fulfilling prophecy, companies are even less likely to consider public listing, and instead will continue to turn to patient private capital as they grow.

α + β = VC

From a performance perspective, venture capital (VC) has consistently driven the most value on a cumulative basis, as multiple industries undergo technological transformations with VC backing. Furthermore, beyond generating outsized returns, venture capital can also provide diversification benefits to an overall asset allocation6.

Recent years have seen great moves being made towards the democratization of access to private assets, turning what was once an asset class almost exclusively available to multi-million endowment trusts into something accessible to investors of all sizes and types. This is timely, as investor portfolios increasingly require novel sources of diversification. The last few years have seen correlations between traditional asset classes narrow significantly, culminating in 2022 as rapidly rising inflation has disrupted the traditionally inverse correlation between equities and bonds.

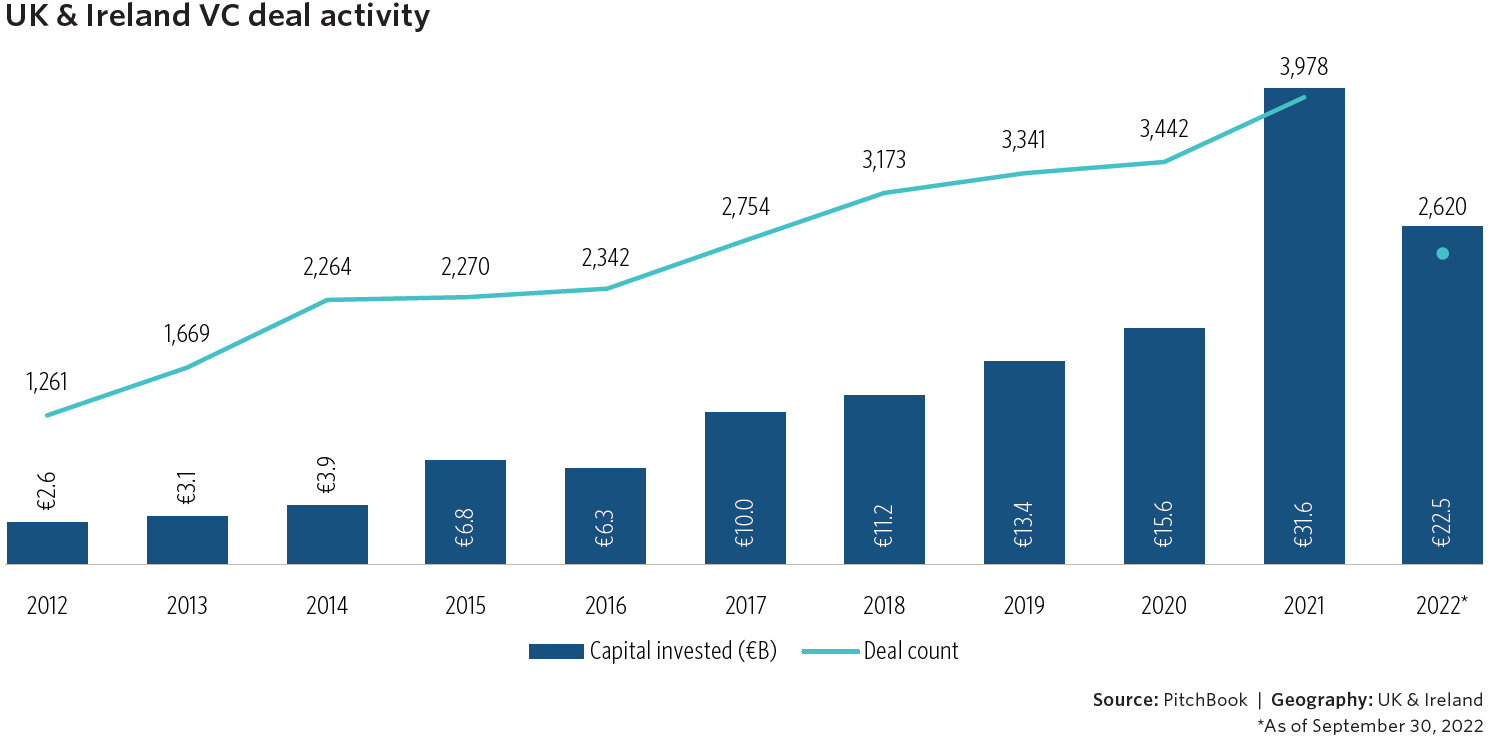

While global financial market volatility has caused widespread uncertainty, VC fundraising and deal activity has, so far, displayed relative resilience. This is a testament to the tectonic shift in how we approach investing for growth, as investors across asset classes have looked to capture the returns offered in venture. VC deal activity in the UK and Ireland in particular has defied the macroeconomic and political uncertainty of 2022, as the pace set through Q3 2022 aligned with the record 2021 figures7.

Conclusion

Evidence that companies are staying private longer and therefore experiencing more of their growth cycle outside the sphere of public markets is mounting. Technology developments are set to keep transforming the global economy and aspects of every industry, and with the number of public companies rapidly shrinking, most of the innovation and dynamism we are seeing in developed markets is happening at private companies. This carries a clear implication for investors: as companies undergo the steeper part of their growth curve privately, an allocation to private markets is crucial.

As investors look to increase their exposure to alternative assets, and particularly private assets, it is likely that we will see a continuation of the increased non-traditional investor participation in VC that we have observed over the last 3 years. Luckily for those investors that don’t have access to the type of capital required to participate as a limited partner (LP), there is an abundance of options in the form of listed investment trusts (ITs) and Venture Capital Trusts (VCT).

The last decade has seen a rise in allocation to private assets within traditional equity ITs, as well as an increased pool of specialist/alternative ITs across an extremely diverse range of private assets, including life sciences, fintech, renewables, digital infrastructure, and space to name a few. According to the Association of Investment Companies (AIC), alternative ITs have grown from £32bn a decade ago to £116bn today, while more traditional equity ITs have lost much of their appeal as managers have struggled to outperform mainstream indices8.

This democratisation and improved access to private assets is all great news for investors wanting to diversify their portfolio away from the broader markets, and gain exposure to exciting growth assets. It’s a trend that’s likely to continue – and even build – over the coming years, as investors continue to adapt to the new normal for growth investing.

1 Growth Stocks: Widest Valuation Gap in 20 Years

2 Healthcare IPOs break record in 2021 as Chinese companies lead Q4

4 Private equity circles fallen stars of pandemic IPO boom

5 The Growing Blessing of Unicorns: The Changing Nature of the Market for Privately Funded Companies